Ishigaki – Samurai Castle Walls

The types of stone wall and features, how they differ, and how to read the walls.

There’s an old saying, “If only these walls could talk…” in fact, the walls of samurai castles do talk, we only have to listen to know what they’re telling us. Here’s how to translate!

Ishigaki 石垣 — the stone walls of a samurai castle — are classified by the stone processing method and techniques for the laying of stone. Looking at the types of stone walling can often provide a hint as to the age of the castle and the approximate time of its construction, the situation under which it was made, the power and the financial position of its lord, and the perceived importance of the section of wall you are looking at. Often the important sections, such as around gates, and along routes taken by visitors and guests will be among the most impressive masonry. Inner sections where such visitors and guests would not see, used a rougher form of construction. By understanding the various types of ishigaki, you’ll understand so much more about the castle and its creators.

The castles of Europe and the middle east are mostly constructed from stone or brick, while only the foundations of the castles of the samurai consisted of stone. Ishigaki were a protective crust of stone around earthen rampart walls or hill faces, often acting as foundations for the defensive wooden superstructures or protective mud-filled walls.

Visitors to samurai castles often head straight for the tenshu, the tower keep, watchtowers, gates and other structures and fail to note such things as the moats, earthen ramparts or even the fascinating stone walls that also define a castle.

The main forms of ishigaki stone wall construction are:

野面積Nozura-zumi (野面積) :

Natural stone with little or no processing.

Nozura-zumi is an older style of wall made of natural, untreated stone, quickly piled and seemingly quite roughly, often with gaps left between the large stones. Indeed, many of the early castles were constructed quickly, as the enemy could attack at any moment, and so speed was of the essence. While it may look rather slapdash and rickety in places, often nozura-zumi walls are less likely to fall than some of the more modern styles. The large gaps allow accumulated rainwater to drain easily, and the roughness of the piled rocks keeps them in place well. Because castle ishigaki are created without the use of mortar or binding agents other than gravity, they are able to withstand earthquakes better than most modern-day wall construction methods. They will move about in times of quake but settle again afterwards.

Uchikomi-hagi (打込接):

Stone that has been split and lightly processed.

Uchi-komi-hagi walls were constructed with partially worked stone, in some cases roughly shaped to fit a wall space. Smaller stones were then used to fill the remaining gaps, forming a visually more appealing wall, with less footholds. The majority of remaining castle ishigaki is uchikomi-hagi, as it was a relatively fast yet effective stone piling method.

Kirikomi-hagi (切込接):

Cut and well processed stone for close fitting.

Kirikomi-hagi walls feature well hewn, carefully and closely fitted impressive stonework resulting in a clean, flat finish. Such work took time and money, suggesting an affluent lord had these made in the peaceful times of the Edo period. As mentioned, often the best masonry work would be visible at gates and along the routes taken by visitors, and so kirikomi-hagi masonry work would be employed in such areas. One problem with kirikomi-hagi walls is that the stonework is too good. There are no gaps for storm water to drain, and so water can accumulate behind the walls, which may suddenly burst under the pressure and collapse. Most Edo period castles feature this type of stonework, as the peaceful times allowed for such fine work. Older examples of kirikomi-hagi work will often reveal the marks of the mason’s stone chisels, and that in turn can reveal the approximate age and skill level of the mason. Deep, random lines suggest a young, strong, yet unskilled worker. Deep straight lines, a young, but reasonably qualified mason. Shallow engravings on a smoother faced stone were probably done by a seasoned worker, while the smoother, almost undiscernible chiselling was done by a professional mason of some years’ experience.

Further classification of ishigaki is made by the actual stone stacking method.

Ran-zumi(乱積): refers to the random stacking of stones in various directions. This usually identifies an older form of construction, done hurriedly.

Nuno-zumi(布積): is the stacking of stones with joints running horizontally, rather like modern day brickwork, and is named for the waft and weave of cloth, or nuno.

Other special stone piling methods include maki-ishigaki 巻石垣, which are extra sections of ishigaki serving as retaining walls, built at a later to support and reinforce a higher wall in danger of collapsing. One of the most interesting examples is the dome shaped ishigaki at Tottori Castle, built to correct the potential collapse of the original section of wall behind it. Another is Shikishi-tanzaku-zumi 色紙短冊積as seen at Kanazawa Castle in which well-cut square and rectangular stone of different type and color are set in a wall, creating a pattern. This is done solely for artistic purposes rather than for any defensive reason.

Basically, ishigaki can be divided into six types by processing method x stacking method .

Classification by Appearance;

Shinogi-zumi(鎬積): Stacking stones so that the corner angles of ishigaki are at obtuse angles of 90 degrees or more. Early castles were rarely square, as they used the natural terrain. Angles were of all degrees, depending on the shape of the hill, river, cliffs or other natural features. This type of corner stone laying is seen in the early period of castle construction, before Sangi-zumi was established.

Sangi-zumi算木積(算木積): Sangi zumi is the stacking of rectangular stones with the long and short sides facing in alternating directions resembling a zip fastener. This technique greatly increases the strength, and the visual image of the wall.

Tani-zumi(谷積)/ Otoshi-zumi(落し積): This practice involves stacking stones at an angle. This style was used occasionally from the very late Edo period to the Meiji period onward. Most tani-zumi stacked walls are ishigaki repaired in the post Edo period years, until as recently as the 1980’s.

Kikko-zumi(亀甲積):Stone is processed into hexagonal blocks like a turtle's shell and piled up as close fitting stone. This is considered the highest level of Kirikomi-hagi, and can be seen particularly at the financially strong Maeda clan’s Kanazawa Castle.

Tamaishi-zumi(玉石積):This is a piling method using round stones, usually gathered from rivers as the main material. Yokosuka Castle in Shizuoka is a very good example of this. Such river stones were rarely used, citing problems with difficulty in stacking, lack of steadfastness due to the lack of contact grip with surrounding, smooth stones, leading to a high rate of collapsibility.

Warai-zumi(Warai-zumi笑い積): A stacking method in which relatively small stones are piled around large stones. It is called “Warai” laughing, because it appears to be smiling with a wide, teeth-filled mouth. In some cases, nozura-zumi, with many gaps between the larger stones, such as at Ogaki Castle, is also called Warai-zumi, resembling gaps between the teeth.

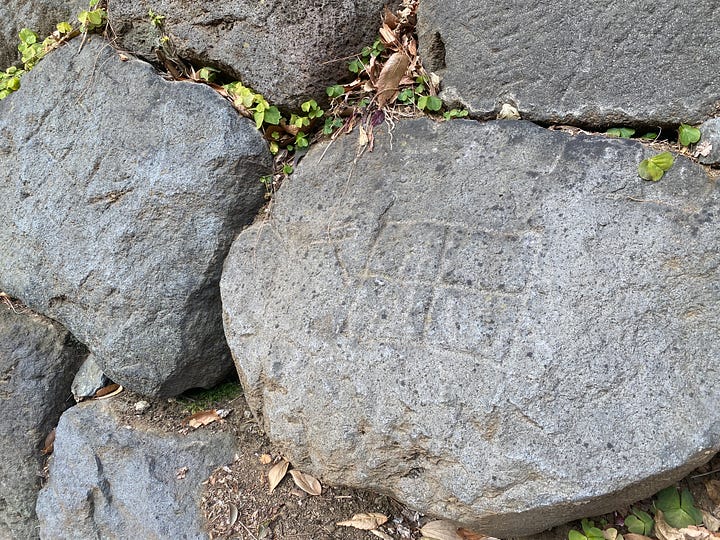

Kokuin Kokumon

Often on the stones of castle walls, especially castles constructed under the orders of the Tokugawa Shogunate, are a range of crest like engravings. These are called kokuin, or kokumon, and are the marks made by the lords “invited” to participate in the castle building public works projects of the shogunate. The members of such groups were usually former enemy, Toyotomi affiliated daimyo of western Japan. In the case of Nagoya Castle for example, 20 such daimyo were brought in to work on the castle.

Ieyasu kept his former enemy close, he kept them under watch, he kept them busy, and he kept them spending their money – finances that could otherwise be used to build up samurai numbers, purchase weapons and stores for war, to possibly revolt against the Tokugawa – instead, the funds were used to build the Tokugawa’s castles. It was a strategy for peace! Because the daimyo were given the plans for the castle to build it, they also became aware of how well it was defended. Its reputation was such that no one ever attempted to attack Nagoya, as they all knew just how strong it was! When building the castle, these daimyo would put their mark on the rocks for two reasons. One was to show that they had built this wall, signing it like an artist signs his work. The other reason was to prevent other daimyo’s work teams from taking and using the valuable hard sourced stones. From these marks it is possible to discover who made the walls, and also to note the quality of skill possessed by the various daimyo in their construction methods.

Why Are Walls Angled?

The ishigaki of Japanese castles are usually built on an angle. The foundations and structures of European castles and Japanese castles are vastly different.

The Ishigaki are built on an angle for various reasons. A wide base tapering inwards towards the top can support a heavier structure. However the main reason is because 20% of the worlds’ earthquakes occur in Japan. The walls being angled is partially because the stones are also positioned on an angle facing inwards. If an earthquake occurs, gravity dictates that the angled stones would fall inwards, thus stabilizing the wall. That such technology existed around 500 years ago is something that amazes me!

Other forms of Ishigaki

Nobori Ishigaki refers to a climbing ishigaki wall, ishikagi built on a slope or incline to prevent the lateral movement of invading enemy, and confining or directing them to other sections, rather like tatebori, the vertical trenches dug up mountainsides for the same reasons. Iyo Matsuyama, Hikone and Sumoto Castles have good examples of these climbing ishigaki, and other examples can be found at Tottori Castle and nearby Yonago, Hyogo Prefecture’s Takeda Castle, Kofu Castle in Yamanashi, Amaga Castle in Nagano City, and Netsu Castle in Tomi City, Nagano Prefecture.

A few Wajo, Japanese castles remaining from the 1590’s Korean Invasion also feature nobori-ishigaki, and it is often believed that these were the earliest form of nobori-ishigaki, later the idea was brought back to Japan and introduced to the above mentioned castles.

Castle fans have their own points of interest in castles, and Ishigaki is one of them. Even for the same castle, the Ishigaki can be stacked differently, depending on the era and place they were stacked, the skill of the daimyo involved in the walls’ construction so they show a variety of expressions.

They are all unique and fascinating, …and if only these walls could speak…

Great article!