Death poems generally refer to short poems written when one dies, a custom unique to East Asia, and particularly Japan. The term jisei (old kanji, 辭世) originally meant “bidding farewell to this world”, and from there it came to refer to short poems that are composed when a person’s life is about to end through natural aged death or through illness, but more often before battle, execution or committing seppuku.

Jisei death poems generally refer to works that have been prepared in advance, but in a broader sense also include works written impromptu on one's deathbed, or works that happen to be the last poem written because its’ author died suddenly with no time to compose another one (such examples are alo known as "zekku"). In terms of content, they focus on emotions and summaries of one's life, thoughts about death and the like. Death poems are traditionally usually emotionally neutral, gracefully and naturally written. Except for some of the the earlier works, often mentioned themes include sunsets, autumn or cherry blossom — suggesting the transience of life — are used instead of mentioning death directly, which was considered inappropriate in such poetry.

Jisei death poems were composed in various forms, such as the two traditional Japanese forms of Kanshi (classical Chinese style poetry, most popular during the early Heian period among Japanese aristocrats). or Waka (classical Japanese poetry of several genres) , in 5-7-5 syllable haiku form, but more commonly in the Waka styled tanka poetry, consisting of five lines of 31 syllables (5-7-5-7-7) — a form that constitutes over half of surviving jisei death poems.

The origins of jisei death poems as a custom is unclear, but in Japan, examples of poems written upon the realization of one’s own death include Prince Otsu on his execution in 686, and the Nara period government official Otomo no Kumagyo (714-731) both featured in the Manyoshu anthology.

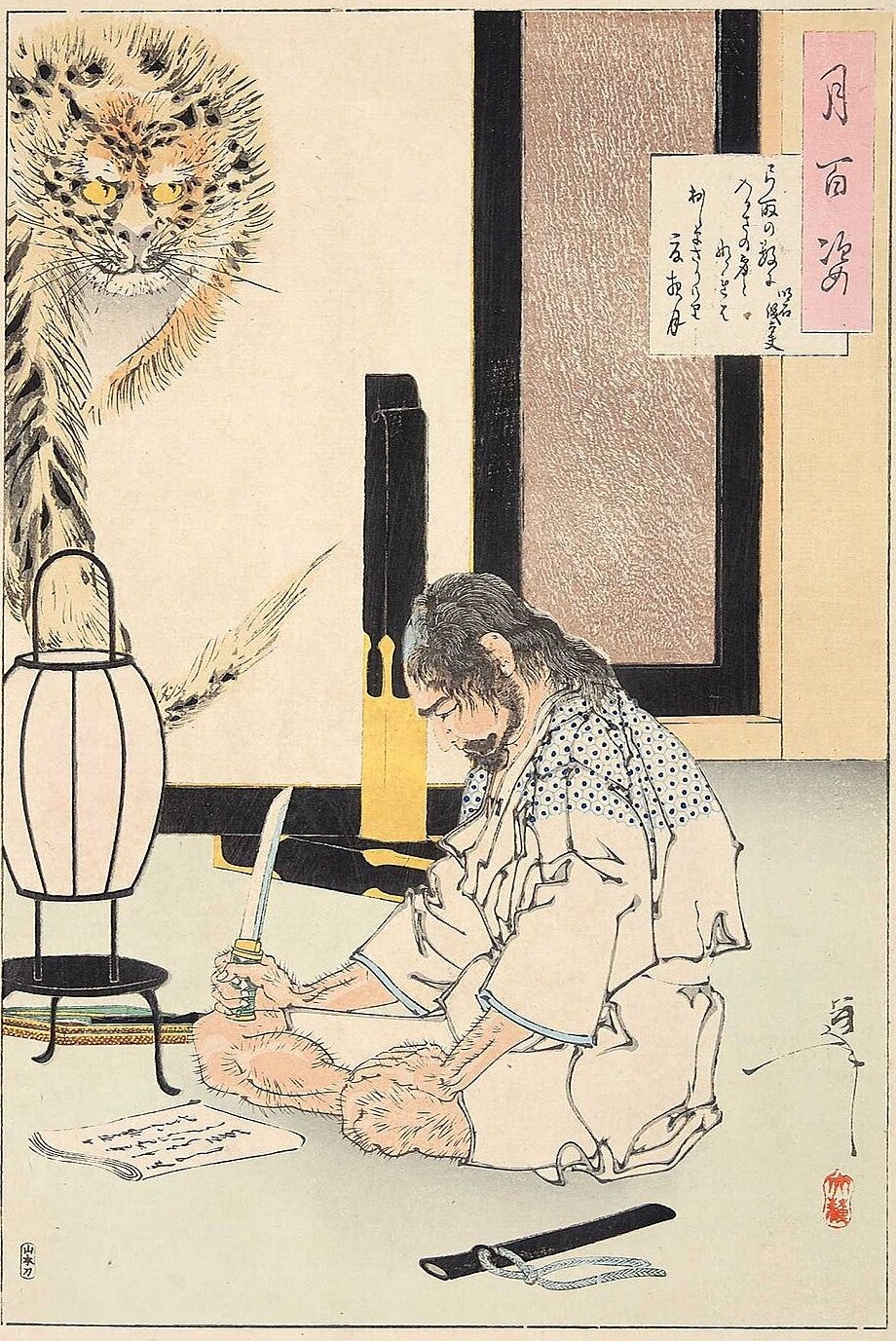

It became especially popular in Japan from the Middle Ages onwards, and became an essential custom for literary figures and warriors in their final days or when committing seppuku. In these cases, the most commonly used form of poetry was waka. This is thought to be influenced by the custom of Zen monks writing down verses as their final works before death.

During the peace times of the Edo period, death poems in the form of verses almost disappeared, and at the same time, it became common for the serious waka form to change into kyoka (light verse) and haiku. As such, forms that could incorporate vulgar elements and humor not found in traditional waka came to be widely used in death poems, delicate poetry that was bright, light-hearted, and depicted death, but beneath the surface there was a hint of something serious. The Edo period therefore arguably marked a new peak in death poem literature. Another characteristic of this period was that people who had no choice but to choose suicide for political reasons often used the classical Chinese poetry form for their death poems, indicating that this form was best suited to expressing one's social or political aspirations.

The poet Kisei left this jisei in 1764;

Since I was born, I have to die, And so,…

Jisei give us an insight into the mind and hearts of the authors as they contemplated their final moments, their past, their present and their death, and reminds us that each day, we are a step closer to our own, inevitable end.

Some Famous Death Poems

Life is but one cup of sake;

Forty-nine years passes in a dream;

I know not what life, nor death is.

Year in year out, all is but a dream.

Heaven and Hell are left behind;

I stand in the moonlit dawn,

Free from clouds of attachment.

-Uesugi Kenshin

Is this May rain dew or tears?

Nightingale,

Carry my name above the clouds

-Ashikaga Yoshiteru

Interestingly, Shibata Katsuie’s jisei is in a similar style;

Fleeting dream paths,

in the summer night,

Mountain nightingale,

Carry my name

Beyond the clouds.

-Shibata Katsuie

Since ancient times, Noma has been the place where lords are slain.

Your retribution will come, Hashiba Chikuzen!

-Oda Nobutaka, son of Nobunaga on his forced seppuku, (mentioning one Hashiba Chikuzen, better known as Toyotomi Hideyoshi!)

Though the sands on the shore of Ishikawa may run out,

the thieves of this world will never run out.

-Ishikawa Goemon

The dew appears

The dew disappears

My life, that Naniwa,

Is a dream within a dream.

-Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Ah, Chikumae,

Just as your blazing reed bonfires burn out,

So too shall this body

- Ishida Mitsunari

Ah, how pleasant! Two awakenings and one sleep.

This dream of a fleeing world! The promising hues of early dawn!

- Tokugawa Ieyasu

More than the flowers that blow the wind, what can I do to hold onto the vestiges of spring?

- Asano Takumi no Kami Naganori (master of the 47 Ronin)

Ill from the journey, my dreams wander across the barren plains

- Matsuo Basho

(This was "written during illness", and is not thought to have been written as a death poem, but as it was the last poem Basho wrote, it is generally considered to be a death poem.)

The summer fields are filled with ghosts, and I am lost in the mist

- Katsushika Hokusai

Despite the seriousness of the subject matter, some Japanese poets employed frivolity, absurdity or humor in their final compositions. The Zen monk Toko (1710–1795) commented on the pretentiousness of some jisei in his own death poem:

Death poems

are mere delusion –

death is death.

Written over a large calligraphic character 死 shi, meaning Death, the Japanese Zen master Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768) wrote:

Young folk, if it is death you fear,

die now!

Having died once,

you won't die again.

Fab, thanks!

You can say through his poem that Ieyasu left this world with way more sense of accomplishment that most.

Tried to understand the meaning of Ishida's words but no success.