Kao (花押) are stylised identification symbols or signs used in place of a handwritten signature. Their origins lie in handwritten cursive writing. A signature in the cursive style is called a soumyo, and a soumyo whose stroke order and shape are so specialized that they cannot be considered normal characters are called kao. The particular stroke order and shape is the result of a conscious act of writing by the person signing the signature to create a unique signature.

Kao arenly found in the East Asian kanji culture regions. There are various theories about their origin, including being from China's pre-3rd century BC Qin Dynasty, the Qi Dynasty (around the 5th century), and the Tang Dynasty (7th to the 9th century). In Japan, kao began to be used from the mid-Heian period (circa 10th century) and was also known as a han, kakihan, or hangyo.

Originally, one's name was simply signed on documents, but in order to clearly distinguish the authorisor from others, the signatures gradually became stylized and patterned, and special shaped kao were developed.

In Japan, people originally signed their names in plain script, or kaisho, but gradually this became a cursive signature in sousho style and known as the soumyo, (cursive signature) which became extremely artistic, becoming the kao. The earliest examples of Japanese kao are found around the middle of the 10th century, and the signature of the Udaishi minister, Sakanoue Tsuneyuki dated around 933 is said to be the first appearance of Kao in Japan.

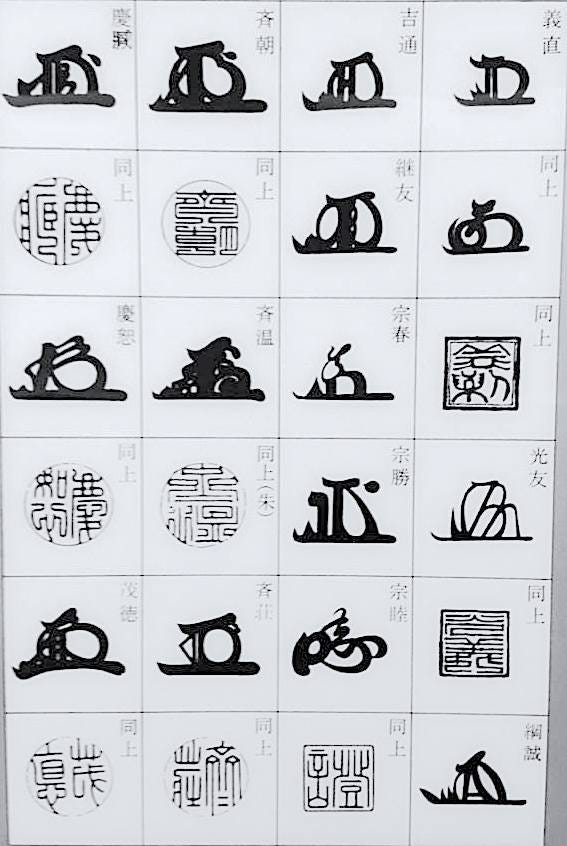

In the 11th century people starting taking the two kanji characters of their name and combining them in a stylised fashion. This was the birth of the nigotai, two-part combination style of creating a kao. Around the same time the ichijitai, single stylised character way of writing a kao first appeared. This style takes one of two kanji of a person’s name and stylises a single character to create the kao. Heian period military commander Minamoto no Yorichika used a combination of the characters taku' and mi. Also, around the same time, single fonts in which only one character of a real name was designed began to be seen, such as the Taira clan’s single character Tadashi kao. In either case, the principle was that the kao was created using one's real name, as a substitute for one's own signature. Although kao originated in aristocratic society, from around the late 11th century kao also began to appear on the documents of the common people. A characteristic of commoner kao at the time was that their real name and kao were written together, because, unlike in aristocratic society, it was not possible to identify someone using only the kao.

From the Kamakura period onwards, as the number of documents issued by samurai increased significantly, so too did samurai use of kao. As a result, a distinct shape and signature method of kao, unique to samurai, was born. This style was different from that of the aristocrats, and was called Bukeyo, while the aristocratic kao was known as Kugeyo. Originally, kao were made based on one's real name, but samurai from the Kamakura period onward had a tendency to imitate the kao of their ancestors and lords, regardless of their actual names. The Hojo clan for example adopted the kao types of Hojo Tokimasa or Yoshitoki, while the Ashikaga clan and their subordinates continued to imitate Ashikaga Takauji's kao, creating a trend known as Ashikaga-sama. During the Muromachi period, most of the samurai kao were of the Ashikaga style.

Another characteristic of samurai kao is that they adoped the common custom of the Heian period, in that their real names and kao were written together. It was customary for elite samurai and warlords to have their staff or scribes write documents, and only sign the kao themselves. Therefore, when determining the authenticity of a document, the nobility placed emphasis on handwriting verification, while the samurai placed emphasis on checking the kao. For court nobles, use of complicated and multi stroke order kao became popular from the late Kamakura period onwards, becoming standardised from the Muromachi period. As a general trend, simple kao were used by middle and lower class court nobles, while stylized and complex kao were used by upper class court nobles.

Zen monks mainly used kao influenced by China’s Song and Yuan dynasties. These were often of a simple shape and were called Zensouyo. Kao based on pictures rather than text are called betsuyotai. Betsuyoutai with bird designs appeared, such as Miyoshi Soei’s waterfowl kao and Date Masamune’ rendition of bird. There were many cases in which a son who inherited the headship of a family also inherited his father's kao, and the Shogunate Ashikaga and Tokugawa families used kao designs that were strikingly similar to those of their respective ancestors, suggesting the kao began to play a role not only as a signature but also as a sign or respect or symbol of a specific status.

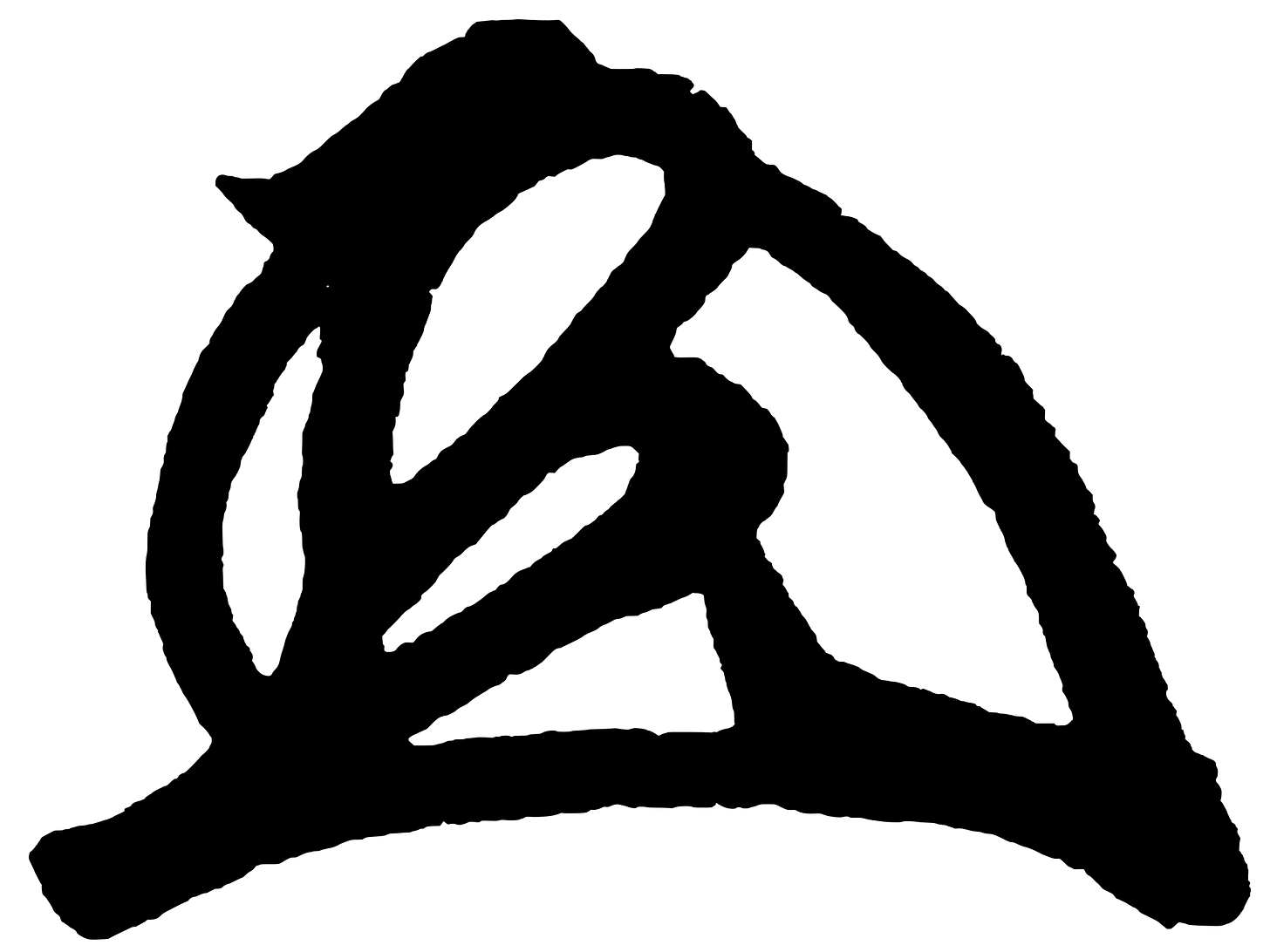

During the Sengoku period, the styles of kao became significantly more diverse. In addition to the appearance of names that were reversed or inverted to prevent forgeries, names began to be created based not necessarily on real names but on common names, surnames, or unrelated characters, such as Ashikaga Yoshimochi and Yoshimasa's ji kao, later Oda Nobunaga's Kirin kao and Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi's 悉kao . Warlord Oda Nobunaga used a particularly artistic, striking kao, said to be a stylized version of the kanji, Rin 麟the second kanji from the mythological creature "Kirin". On its own, rin can mean "genius" or "shining" and is believed to symbolize a perfectly governed world. Same too with Hideyoshi who used 悉... meaning “To know, learn about, comprehend completely”, or, “to do one's utmost”.

Kao-gata, are a type of engraved kao ink stamp used since the Kamakura period. These became widely used during the Sengoku period, and even more popular during the Edo period. As such kao-gata began to be used in the same way as hanko seals, and the use of kao decreased. Particularly among the peasant class, kao ceased to be seen around the middle of the Edo period, and seals began to be used exclusively.

In 1873, a Meiji period edict was issued stating that certificates without a registered seal could not be used as evidence in court. Although kao were not banned as such, they almost disappeared and were replaced by seals. However, since the Meiji era, it has been customary for government ministers to sign signatures at cabinet meetings in the Japanese government using kao. Since many cabinet ministers rarely use kao for purposes other than signing signatures at cabinet meetings, there are many cases in which a kao is prepared upon taking office.

Kao collectors scour antique shops and markets seeking new and interesting Kao, particularly those of Japan’s historical figures.