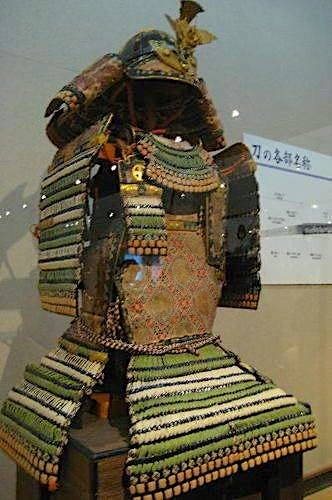

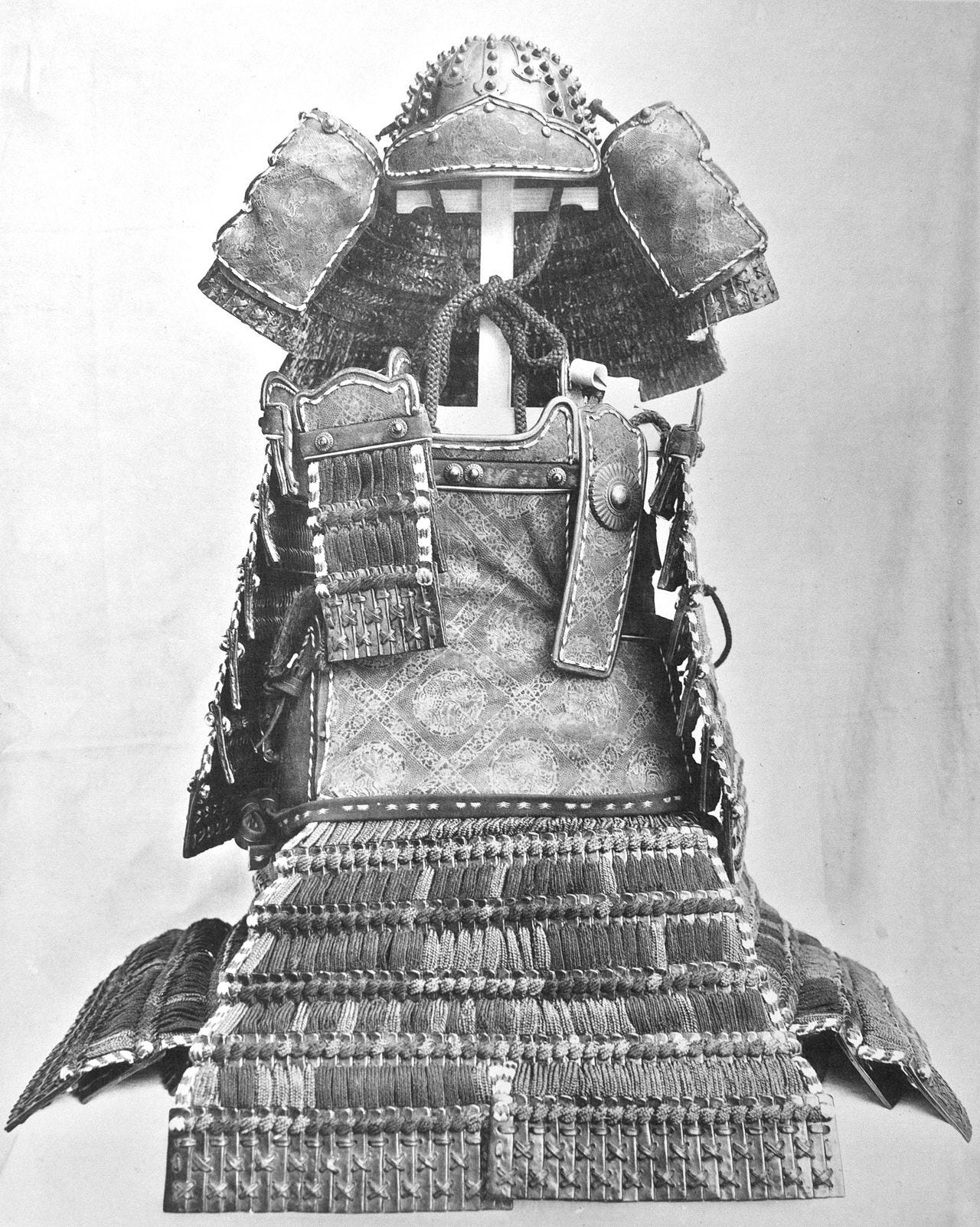

O-yoroi, or Great Armour, was an early type of loose fitting, box-shaped samurai armour appearing in use primarily from the 10th to the 12th Centuries.

The O-yoroi weighed about 30 kilograms, being made mostly from five to eight centimeter long lacquered scales of steel called kozane, and pierced with multiple holes through which silk, cotton or hemp braiding was laced to form rows and layers of protective steel scale plating. To lessen the weight, lacquered scales of nerikawa, rawhide leather, were either interspersed with the iron scales, or covered the less important sections. These sets of armour were expensive and time consuming items to make, with a set of O-Yoroi taking around 9 months to complete, and using as many as 2,000 kozane scales.

Early O-Yoroi armour was heavy, bulky, less flexible than later models, and therefore more difficult to fight in. O-yoroi can therefore be likened to a tank, it was mainly designed with horse mounted archers in mind, rather than infantry. When mounted, much of the weight of the box shaped body armour or dou was born on the saddle, relieving much of the weight from the shoulders.

Wearing the O-yoroi

Once dressed in kimono under-robes and hakama, the left, then the right suneate shin and knee guards were first fitted, then (from the Kamakura period) the haidate an apron-like thigh protector is tied around the waist. Next, the left, and then — if worn at all— the right kote being the armoured sleeves worn under the dou or body armour were fitted. As with the the suneate shin and knee guards, the left side kote was fitted first, as the left side faced the enemy. The right side of the “U” shaped dou was open, and so the waidate, a steel scale or leather plate with further rows of scales hanging loosely below it, were used to close off this opening. This was tied to the right side of the body before the dou was fitted and tied shut, encompassing the body. Like the waidate, the rest of the dou featured three sets of laced scales in rows hanging below the main body armour. This was part of the upper leg protection called the kusazuri, or literally “grass scraper”.

The helmets were bowl shaped crowns made of multiple triangular pieces of steel, hammered into shape, and riveted together with large protruding headed rivets. They featured the distinctive swept back ear-like wings known as fukigaeshi, which are said to have been to deflect arrows and protect the face, and multiple tiered rows of protection around the neck. Often copper antler-like decorative devices called kuwagata were fitted to the front.

Other pieces included the O-sode, large, rectangular shield-like shoulder guards. Early examples of the O-yoroi show the scales were often bound and then lacquered, while later pieces were individually lacquered before lacing to provide greater flexibility.

While most samurai armour was not uniform as such, but ordered to the tastes and affordability of the samurai themselves, early O-yoroi lacing styles and colours indicated the ranks and clans of the wearer. Higher ranked samurai had tightly laced armour, while lesser-ranked samurai had loosely laced protection. Later, when loosely laced armour became the preferred style, rank was designated by the colors of the nodowa, throat protector lacing. Interestingly, very few examples of the much preferred red silk lacing and black have survived, as exposure to sunlight would hasten the deterioration of the silk, an effect of the red and also the black dyes used, whereas the dark indigo and green moegi colours seem to have helped preserve the silk better.

In some cases, sheets of printed deer skin covered the scales to further protect against dirt and mess, while also preventing rust and corrosion. By the Sengoku period, heavily laced armour was later shunned in favour of lesser lacing, as it reduced construction time and costs, decreased weight, allowed for greater ventilation, was not as heavy when wet, nor as difficult to clean of mud and blood.

Towards the end of the Heian Period, the difficult to wear O-yoroi developed into the more convenient, easy to wear and more battle ready Do-Maru Yoroi, better suited to closer combat fighting on foot.

In Depiction

Despite the many changes and developments in armor over the years, many battle screens and scrolls depicting Sengoku, or warring States period battles show the combatants fitted in not contemporary styles, but in the classical O-Yoroi of old. In the peaceful Edo period, the O-yoroi style once again became fashionable during the mid to late 1700’s and many fanciful neo-O-yoroi were created.