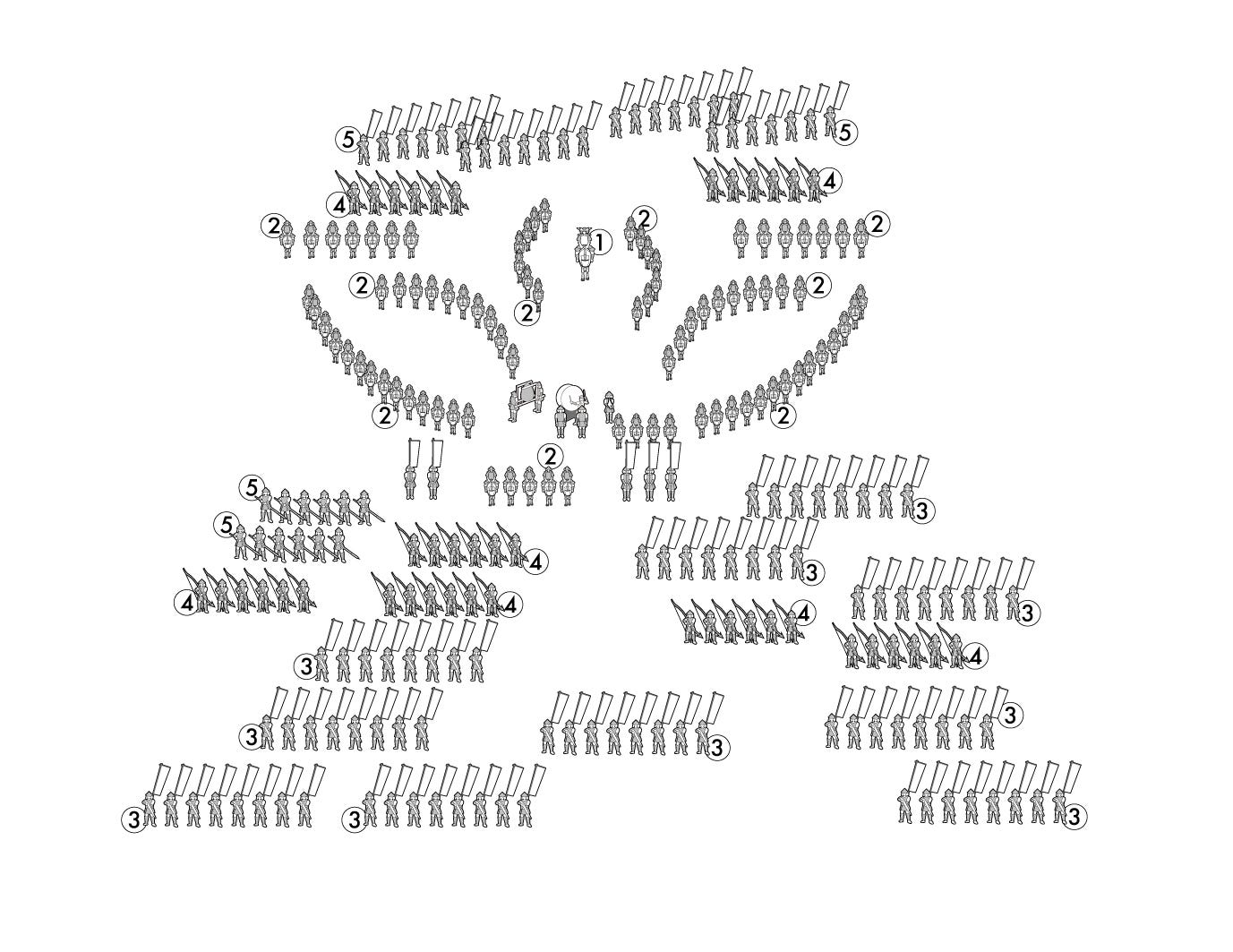

Throughout samurai history, many elaborate battle formations with fanciful titles were developed, although many were not properly formalised until during the peaceful Edo period that was forged by the battle of Sekigahara in 1600. Loyal vassals and clan members would occupy strategically important points within these formations, while the warlord daimyo or leader would be stationed towards the rear in his war camp. From there he could control the battle through the use of visual standards such as flags or visual devices, conch shell horns, bells, gongs or war drum signals, and through the dispatch of mounted tsukaiban messengers with specific orders for the captains of the many components of a formation to follow.

The commander in such cases was seen as the main rallying point, and indeed his presence would have quite an effect on the outcome of a skirmish, rousing his men into fighting harder, as well as psychologically upsetting an enemy. If the leader was taken or killed, it usually signified the end of a battle, as his men would flee or simply capitulate and in many cases would often be absorbed into the victor’s forces if not executed.

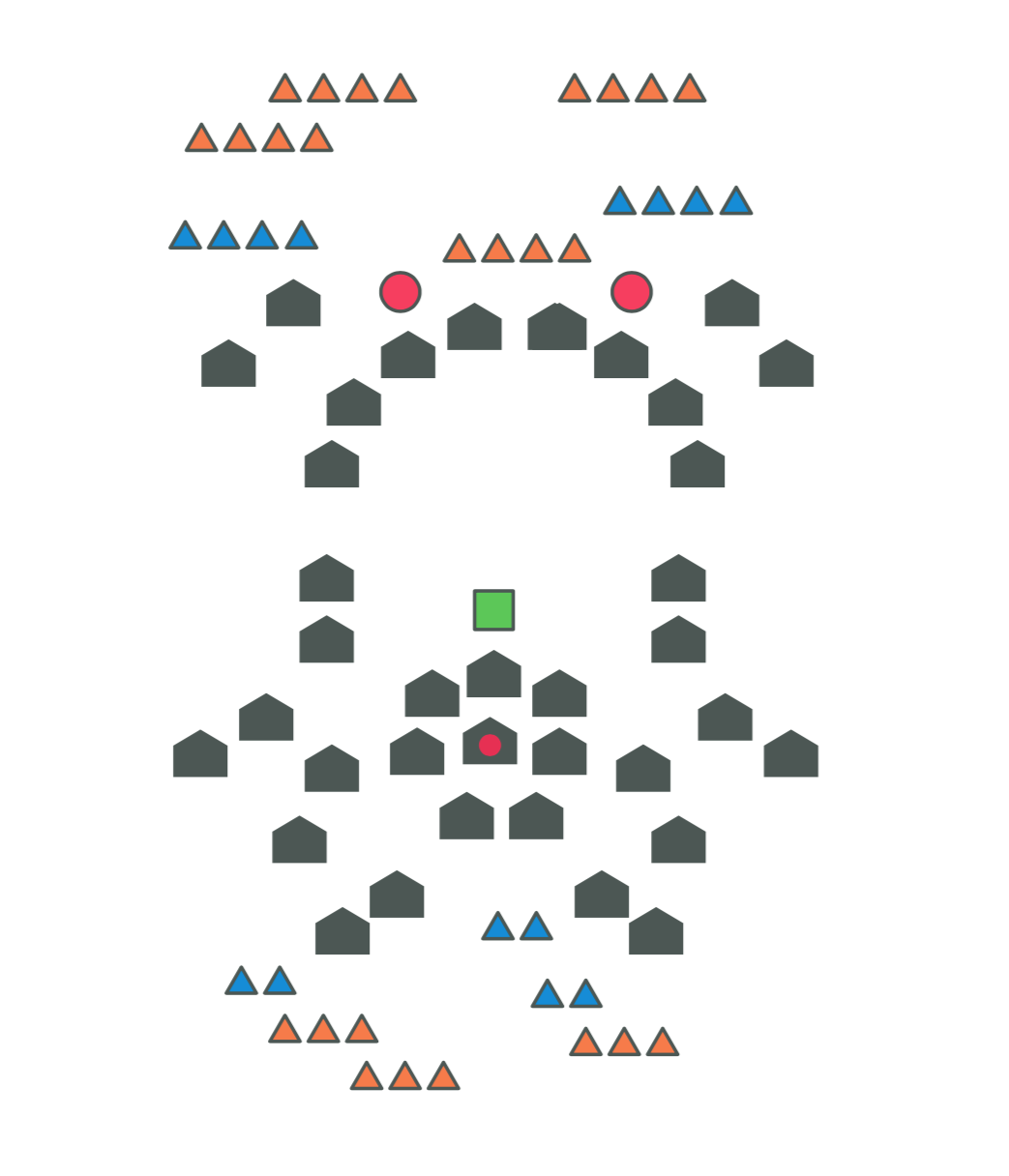

The hoshi no jin arrangement was one of the older Japanese styles of field battle formations. Highly mobile, it was shaped like an arrowhead with lightly protected flanks. It was used primarily to drive deep into an enemy’s ranks. Archers, and later gunners, would open a hole in the enemy’s lines, allowing the armed warriors to enter.

When faced with either the hoshi or kakoyoku (crane’s wing) formations, the koyaku no jin (cattle yoke) formation, named due to its resemblance to the yokes fitted to cattle, was often employed. The twin rows of frontline forces could receive the initial attack and reveal the enemy’s intentions, allowing the following lines of fighters to then counteract the attack by changing positions to either envelop the enemy, or even change formations for a different strategy.

The saku no jin formation, a circular model likened to a keyhole shape, was considered one of the best field assemblies formed when facing the hoshi formation, and easily formed from the koyaku no jin arrangement. The multiple angled rows of frontline gunners and archers were designed to meet the initial hoshi formation with a crossfire of bullets and arrows. Pressing forward, the circular ranks could indent those of the enemy while protecting the daimyo leader.

Based on the patterns of birds in flight, the ganko no jin formation was another easy to form and highly flexible battle pattern, featuring solid lines of marksmen supported by archers, with banks of samurai surrounding the general and a rear guard complete with archers and musketeers. This was a basic, yet formidable order.

When up against a numerically superior enemy, the gyorin no jin model was adopted. Resembling a fish, hence its title, the gyorin formation was used to bulldoze a small section of the enemy in order to break their ranks, rather like a snub-nosed hoshi, or arrow formation.

The kuruma gakari no jin was a formation favored by the Uesugi at Kawanakajima, and consisted of well-trained troops in a spoke-like order radiating from a central marker point. The “wheel” (as the name kurumasuggests) would advance while rotating, so that fresh troops could continually take the place of those in the vanguard, which would then be rotated out.

There are many variations of the above-mentioned formations with equally fanciful names and imagery, affording the samurai the adaptability to face various situations such as terrain, weather, enemy numbers, and so on. Due to the samurai penchant for being first into battle, these formations were often broken as personal valour was sought and as confusion in the heat of the battle reigned. During the peaceful times of the Edo period, samurai armies would often gather in full armour to further develop and practise maneuvers in these formations just in case the unlikely event of war ever broke out again.