Japan would have to rate among the top, if not THE top, most punctual nations in the world. All trains, subways, even busses run like clockwork! If a party invatation states the festivities will begin at 5 and end at 8pm, you will be there at 5, and will go home at 8! The Japanese have long been meticulous record keepers. Often historical records make note of the times as well as the dates. Various religious and political rituals took place according to auspicious times. Records chronicled for example, how long a samurai’s audience with the shogun lasted, what time someone departed from Edo, or the time battles took place, and so on.

So how did they keep time in the days of the samurai? The position of the sun was always one way of telling the time, but in fact official timekeeping began during the reign of Emperor Tenji (668-672) at his capital in Omi Otsu no Miya, east of Kyoto. According to the Nihon Shoki the Ancient Chronicles of Japan, the Emperor invented a gravity fed water clock. Water drained from a main tank to smaller tanks, and the water level could be used to tell how much time had passed while the clock would announce the hours with bells and drums.

The time was also regularly announced in the big cities, Edo, Kyoto, Osaka, Kanazawa Nagoya and others by networks of castle drum or belltowers, which signalled important times. Later in cities such as Osaka, a canon was fired at certain times of day. As for how time was actually calculated in order for castles, temples etc. to know when to ring the bells, there were a number of other ways in which time was counted. Shuri Castle in Okinawa for example had a water clockand a sundial to tell the time, which was then announced to the castle and the city by drums.

Besides water clocks, Japan had fire clocks! Candles with hourly timer markers on them, or smaller candles which were counted as they burned to keep track of time. Incense clocks were often used, particularly in the Edo period. Incense clocks were trays of sand with moveable hour markers set at intervals and adjusted 24 times a year to match the changing seasons. A trail of slow burning incense showed the time. In the entertainment districts, such as Edo’s Yoshiwara, a client’s time with a courtesan was measured by how many incense sticks had been burned, and the client was charged on that basis.

The time frames themselves were also very much different from what we have today. Daytime consisted of six koku 刻 — often referred to as “hours” and witten as 時 ji, or 時分 jifun in old documents —and night another six koku, a total of 12 koku per day, each koku being around two modern-day hours. On a clock face or time chart, midnight was at the top, noon at the bottom, with sunset to the left and sunrise to the right, based on an ancient Chinese system introduced to Japan in the seventh century. Early Japanese time keepers noticed that these seasonal markers were not in tune with Japan but with northern Chinese patterns, where the calendar had originated. Scholars therefore recognised the need to regulate the lunar calendar against the solar year so that the seasons would not drift. Daylight and darkness remained split into six equal segments, but depending on the seasons, as daylight grew longer or shorter, so too did the koku. In winter, with less daylight, the daytime koku were shorter, and the night time koku longer. This was reversed in the summer months. Japan’s central government then established an astronomical bureau to manage and reform the calendar and times as needed.

Each “hour” was named after one of 12 animal zodiac signs, starting at sunrise with the hour of the rabbit, followed by the dragon, snake, horse, goat and monkey. From sunset was the hour of the rooster, the dog, pig, rat, ox and the tiger. Each zodiac was also allocated a number that could be used to announce the hour by strikes of a bell, although the strikes of the bell did not match the actual hour as such. The bells counted the hours down from nine to four, and then returned to nine again. Midday, for example, was the hour of the Horse, noted with nine strikes of the bell at noon, and also at midnight. Eight bells indicated either early afternoon and very early morning, seven bells chimed either late afternoon bordering on dusk or the hours approaching dawn while it was still dark out. Six bells signified sunrise or sunset, Five bells sounded in the early morning and the early evening, four bells would be heard late morning or late evening.

People in old Japan appear to have risen before dawn to begin their daily preparations. While on the road, travelers often departed a town around dawn, suggesting they’d awoken earlier, eaten breakfast, packed and prepared for departure, and would arrive at their next destination around dusk.

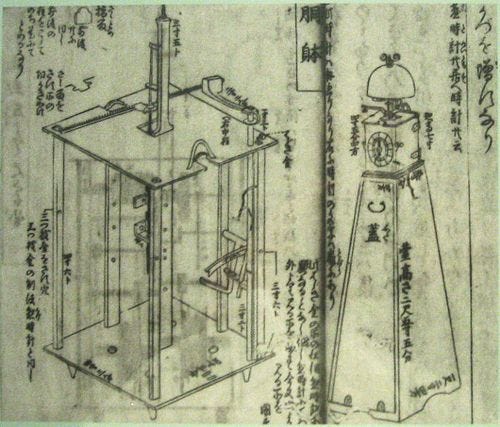

When first introduced to Japan by Europeans in the late 16th century, mechanical clocks became very popular, although they could only be afforded by the most affluent of daimyo. Western styled clocks seemed strange to the Japanese as they measured time in 24 equal hours and ignored natural events like dawn and dusk, and so they were modified to suit Japanese sensibilities and reengineered to allow for these shifts in the Japanese koku hours with the seasons. As such, the small weights which drove the clockwork had to be adjusted every few days, to accommodate the days growing longer or shorter.

By the late 17th century, Japan had a standardized calendar and a single time zone for the entire country. Tokugawa astronomers became accustomed to Western clocks and the 24 hour system during the 18th century, as they measured the motion of heavenly bodies along celestial arcs and timed star transits, noting that the universe behaved more like an equal-hour timepiece than an early Tokugawa period variable clock.

In the Meiji period, Japanese society opened up to international standards, and Western timekeeping practices became associated with positive values such as convenience, social progress, science, and enlightenment. Another advantage for the Meiji government was that it shifted people away from antiquated superstitions and and divination practices. Because of this, the Japanese government mandated the use of the 24-hour clock in 1873.

Since then Japanese watchmakers such as Citizen, Seiko, Casio and others have continued to keep time the world ticking, their timekeeping techniques are second to none. The Japanese penchant for precision and punctuality has since stood the test of time and continues to run like clockwork.

It’s fascinating how they figured it out, and that the Japanese and Western systems evolved separately but both had more or less 24 hour turnarounds. That’s great Wadokei, love the face with its elegant script!