The feudal period social class system known as the Shinokosho, was abolished 155 years ago today, August 2, 1868, as part of Japan’s modernization under the Meiji Restoration reforms.

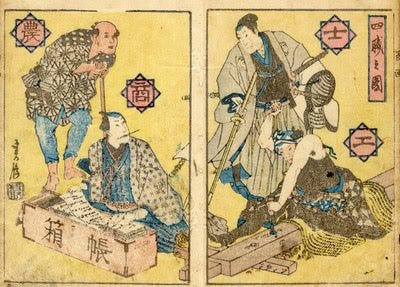

The Shinokosho, or Four Divisions of Society, were composed of the Shi, being the warrior caste, the No, or farming peasants, Ko referred to the craftsmen and artisans, and the Sho being the merchant class. The Shinokosho concept of was adopted by Japan in the Nara period, (710 to 794 ) and properly codified by the mid -17th century at the latest.

Even at the peak of the samurai period, only 7-10% of the population were of samurai class. The bulk of the population at around 80-85% are believed to have been farmers, while another 5-8% are believed to have been merchants and craftsmen. The remaining 1.5% were Shinto and Buddhist priests, and another 1% were the outcasts.

Despite being the minority, the order was established with the samurai at the top, enforcing their status as rulers, protectors, scholars and civil administrators, while at the same time placing emphasis on them to practice restraint as they were to set an example for all those below them. The farmers were placed second because of their importance in providing the essential foods that sustained society. The peasants’s high ranked official status presumably made them feel better about their miserable and over-burdened lives.

Craftsmen and artisans were ranked third as they produced goods and items necessary for daily life. These artisans and in many cases certain merchants were sometimes solicited by the daimyo lords and samurai of wealth from whom they received official appointments and preferred business. Below the craftsmen and artisans were those who made money on the efforts of the others, the merchant class, those who sold the foods and goods produced by the farmers and craftsmen.

During the early Sengoku, Warring States period, the difference between warriors and farmers had become ambiguous as farmers were often conscripted by warlords in order to bolster numbers of armies. The late Sengoku period became a turning point when Hideyoshi’s sword hunt in 1588 completely separated samurai from the farmers and disarmed the peasants, fixing their occupations and status. However, in the mid Edo period, the development of the monetary economy and industries caused merchants to have a greaterinfluence on politics and the economy, and samurai often became economically dependent on merchants for lending. For this reason, some merchants were given the same treatment and rights as samurai.

The classes were not set by wealth or capital, but by Chinese influenced Confucian standards and moral purity. Although the Imperial family members, the Kuge, (aristocratic nobility) Shinto and Buddhist priests, and the outcasts, including the Eta, Burakumin and Hinin were not classified within this set of four. These classes of society were decisive in outlining the privileges, rights, restrictions and responsibilities of the classes that worked to stabilise Edo period society. Marriage between the castes was socially unacceptable, although there were cases of this occurring.

The hierarchy of these Edo period social classes was particularly rigid. Sumptuary laws were enforced to keep the increasingly wealthy shonin — the merchant class including anyone who worked for these merchants, such as shop assistants and even domestic servants — in their place. Rules dictated what styles they could wear and even the colours, the design of their house too was controlled, and even though these merchants made the economy function, such people were known to have dabbled in unsavory pursuits such as money-lending and speculation, and other equally intangible work like trading and shop-keeping that the samurai class were supposed to have found abhorrent. The four hereditary categories were not socioeconomic classes, as wealth and standing did not correspond to these categories. Indeed there were many merchants, and even some farmers who became more affluent than many samurai.

That this system was only abolished just 155 years ago today highlights the fact that Japan’s feudal system is of a not too distant past, and as recently as 40 years ago, until the mid 80’s, to a degree, still influenced Japanese society. It all ended on this day in 1868, making it a case of…class dismissed?

Very interesting. I didn’t know about much of this, including the outcasts (I’ve now looked them up).