In the mid 13th century, the great Kublai Khan, the leader of the Yuan Dynasty Mongolian Empire, had captured large swathes of the Asian mainland and in 1266 finally obtained the submission of the Korean Goryeo Kingdom. He then set his sights on conquering Japan. The Khan sent an envoy to the Shogun in Kamakura suggesting the Japanese acknowledge the Great Khan’s supremacy over Asia, and to concede to the Mongols.

The Shogunate had since become puppets to the Hojo clan regents, who, through various schemes, had wrested so much power they no longer consulted the Shogun nor even the Imperial Court regarding their actions. The letter was ignored. A following, more threatening letter was dispatched in 1267.

Each time, the letters were shown to the regent, Hojo Tokimune in Kamakura, and to the Emperor in Kyoto, and although there was much debate on the topic, the Shogunate refused to comply, mostly ignoring them as they did with the following envoys who arrived in March 1269, September 1269, September 1271, and in May of 1272.

Angered by the lack of respect shown, the Mongolian forces planned an attack on Japan. An invasion fleet of 900 ships carrying some 33,000 Mongol warriors was sent to take Japan by force. The invasion fleet was delayed for three months before attacking first Tsushima Island, then Iki Island where the larger, fiercer Mongolian troops destroyed the smaller samurai units before attacking Hakata in Kyushu.

No reliable records of actual Japanese troop numbers remain, and both sides greatly exaggerated one another’s figures. For example, Mongolian records state the Japanese had 102,000 troops, while the Japanese claim to have been outnumbered at ten to one. but modern researchers estimate their total numbers at around 4,000 to 6,000, while it is believed that the invasion force was composed of 15,000 Mongol and Chinese warriors, 7,000 Korean soldiers, and 7,000 Korean sailors, for a force of around 29,000.

The Mongolian fleet arrived at Hakata Bay on November 19, not far from the then Kyushu capital of Dazaifu. The Japanese plan of defense was simply to face them at every point with appointed vassals of the Shogunate. A wild battle was fought on the beaches the following day. When the Mongols attacked, the samurai were far from ready. The Japanese force’s commanding general maintained his position to the high ground at the rear, and directed the various detachments with signals from war drums and horagai conch shells. The hopelessly outnumbered mounted samurai with their bows and arrows, their quaint one-on-one combat style, and lack of experience in moving and controlling large armies failed them. The Mongols possessed superior weaponry, fire arrows, gunpowder packed ceramic shell grenades, rockets and a no-holds-barred attitude to warfare.

The samurai’s “polite” rules for engagement, taking turns at advancing while mounted, and individually, loudly announcing their names and ancestry, before inviting the opposition to attempt to take them in single combat, were of no match for the marauding Mongols.

When a Japanese commander shot an arrow to announce the beginning of battle, the Mongols burst out laughing. The arrow, intended only as a signal for war, had been shot high and wide, as per the samurai rules of initial engagement. The invaders took this as a sign of the Japanese inability to shoot an arrow at them.

The Mongol units then advanced noisily in dense packs surrounded by protective shields and with their weapons held at the ready. Rushing forwards, they would tackle any samurai getting in their way, overpowering and killing them instantly. As they advanced, they made use of a technical innovation that modern day people would recognize as early grenades. The Mongol invaders threw paper, ceramic and even iron casing bombs at the Japanese, terrifying the samurai horses and making them uncontrollable. The men too were frightened by the thunderous explosions. According to one report “Their eyes were blinded and their ears deafened so that they could hardly distinguish east from west.”

The battle lasted for only a day and the fighting, though fierce, was uncoordinated and brief.

The Mongolian strategy, ferocity and firepower put fear into the Japanese and mistaking the late sudden Japanese retreat for a defensive attack strategy, and not wanting to be ambushed in the night, the Mongolians returned to their ships. That night a great storm hit the area and many Mongolian warships were sunk, smashed against each other, beached or destroyed on the rocks. The survivors were quickly dispatched by the samurai. The rest limped home. By some accounts, around 200 ships were lost. Of the 30,000 strong invasion force, an estimated 13,500 men did not return.

The Second Invasion

In 1279, Kublai Khan ordered another mission be sent to Japan. On arriving on Japanese shores, the messengers were summoned to Kamakura, seat of the Japanese government, and all five ambassadors were swiftly beheaded. Their graves can be found at the Joryu-ji Temple in Fujisawa, Kanagawa Prefecture. Another five ambassadors were sent to Japan in July of 1279 and these men too met a similar fate, being executed in Hakata.

The Khan having since conquered China’s Song Dynasty, was now able to launch a larger force against the Japanese. In anger, the Khan sent a 4,000 strong armada ferrying some 140,000 warriors (again, most probably exaggerated figures) to Japan in 1281. This time an estimated 40,000 samurai were ready. The invaders arrived in two lots, one of which made landfall and went as far inland as Dazaifu City, about 15 km south of Fukuoka.

As the two fleets combined, they advanced on Taka Island, capturing it, then advanced on Hakata, ensuing in a two-week battle. To their credit, the shogunate had expected this second coming, and had ordered a series of defensive fortifications be built, and a stone and earthen wall, two to three meters in height, three meters thick, and at a length of about twenty kilometers constructed along the coast in an attempt to prevent any further attacks. Large stakes were driven into the sands at the river mouths and beaches at potential landing sites.

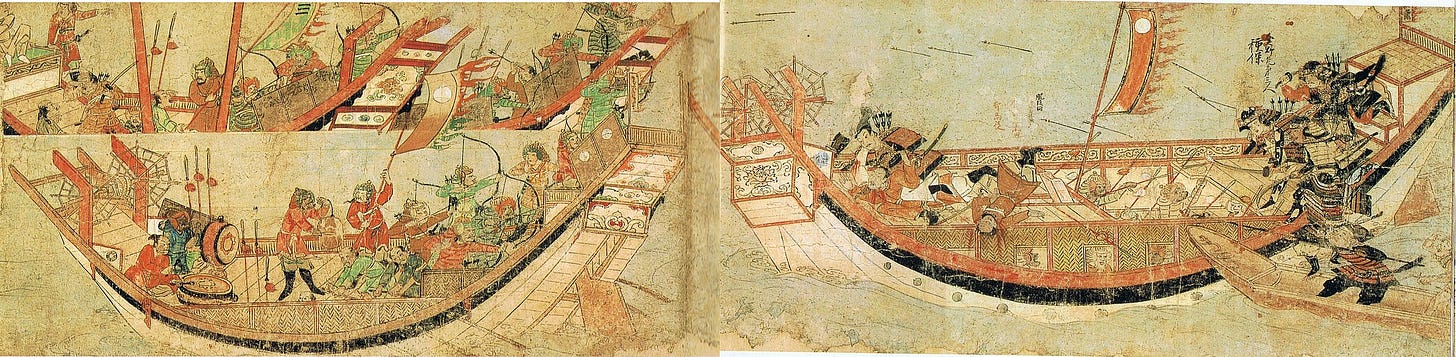

During the battles the use of explosive bombs fired from catapults, and possibly cannons too were used, as the Taiheiki war chronicles mention a bell shaped weapon that “Made a noise like thunder and shot out thousands of iron balls”. Illustrations of bombs are depicted in the Mongol Invasion scrolls, and archaeological discoveries have confirmed the existence of Mongolian explosive devices. The Kyushu Okinawa Society for Underwater Archaeology discovered multiple bomb shells in a shipwreck off the shore of Japan and X-rays of the bombs show they contained gunpowder and scrap iron shrapnel. Alternatively, the Mongols noted that Japanese swords are long and extremely sharp, and that the combination of a brave and violent samurai and a Japanese sword was a threat.

Some Mongolian ships attacking Hakata made it ashore but were unable to make it past the defensive wall and were driven off by arrow fire. On August 12, the Japanese made repeated overnight small raids on the Mongolian fleet. The Mongolians responded by fastening their ships together with chains and planks to form defensive platforms. Many of the ships used by the mongols are believed to have been riverboats, not really suitable for rough seas, and particularly not during typhoons.

On August 15, a great typhoon struck the fleet at anchor and destroyed it. The typhoons that sprung up in Japan's time of need were called Kamikaze, Winds of the Gods. Once again, the Mongol attack ships in the harbor were sunk and destroyed, and the troops that had made landfall were routed. The Japanese believed the Gods had once again come to their assistance, and the Divine Winds, the “Kamikaze” were to thank for their savior.

After the typhoon, the Mongolian commander chose the best remaining ships and sailed away, leaving more than 100,000 of his troops to the mercy of the Japanese. After being stranded for three days on Taka island, the Japanese attacked and captured many thousands. They were taken to Hakata and killed. Korean sources claim that of the 26,989 Koreans who set out with the Eastern fleet, 7,592 did not return. Chinese and Mongol records indicate a 60 - 90 % casualty rate.

This second attack also being halted by typhoons simply supported the Japanese belief in being a nation favoured by the gods, and that they would never be successfully invaded nor defeated, a belief that remained Japanese foreign policy until the end of WWII.

Prior to the typhoons appearances in the first and second attacks, large swarms of dragonflies were noted. This was seen as auspicious, and the dragonfly was adopted as a samurai symbol of success. Often on samurai arms, armour, and particularly clothing, you will find depictions of dragonflies. Dragonflies only ever fly forward, i.e., they never retreat. Yet another reason for the dragonfly being a popular symbol of the samurai was the name of the flying insect in Japanese. Although they are called "tombo" now, the old pre-Meiji era name was "Katchi-mushi". Katchi means "to win!" Ideal for the samurai!

The devastation suffered by the Mongol army from the violent forces of nature had a lasting effect on their future expansion. Likewise, the Mongols had a lasting effect on the samurai too, who borrowed from the invader’s tactics becoming mostly infantry swordsmen who used the bow as a secondary weapon, rather than cavalry mounted bowmen who used swords as a secondary weapon. Indeed, the samurai sword underwent a great deal of development and improvement following this encounter.

The Great wall built by the samurai in 1276 was excavated in the 1930s. Parts of the wall, an incredible feat of construction for the time, can still be viewed around Hakata Bay.

Interestingly, the Mongolian attacks, although stymied by the Divine Winds, caused the eventual downfall of the Kamakura Shogunate. Following the attacks, both the samurai and the priests petitioned the government for compensation. This battle was a defensive one, and as no spoils of war were procured, the Shogunate had nothing to share. What little money the Bakufu had left went mostly to the priests who had more political clout than the warrior class, and who claimed their intervention and prayers brought about the miraculous typhoons that destroyed the invaders. The cost of building the wall and the following three-month long defense of the Empire was never re-payed. Understandably the samurai became greatly dissatisfied with the government, and a 15-year civil war ensued, leading to the collapse of the shogunate. In its place the Ashikaga clan would seize power and continue to rule for the next 250 years, drawing inspiration from the Kamikaze legends.

A result of this war was China’s growing recognition that the Japanese were brave and violent warriors and invading Japan was futile. Ming Dynasty rulers considered invading Japan a number of times, but each time thought the better of it.

During World War Two, the Japanese forces again invoked the legendary powers of the Kamikaze to protect their island nation as they fought the Allied Forces across the Pacific, allowing the western world to know of the might of the Kamikaze.

I guess the timing, & that it happened twice, was remarkable even if the context was many storms.

Interesting read, thanks Chris. How frequent were typhoons generally in those times?