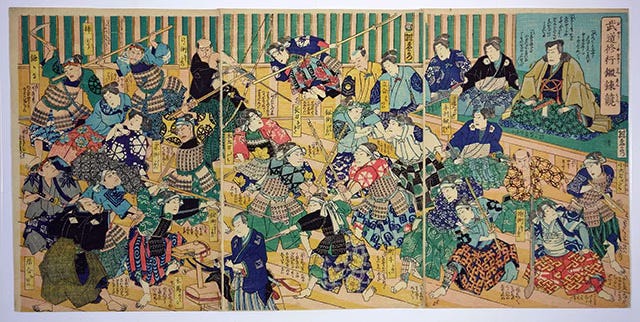

Musha Shugyo, Samurai Warrior Training

Travels undertaken to develop martial knowledge, skills, and the mental strength required of a samurai, in order to improve themselves.

Musha Shugyo, or Warrior Training, was a practice whereby a young samurai would leave their home, school or clan with permission granted by their home domain, and usually alone, travel across various parts of Japan, improving and enhancing their skills while learning about the many different martial schools. Musha Shugyo was a pilgrimage undertaken to acquire the knowledge, skills, and mental strength necessary for a samurai, including martial arts, in order to improve themselves. Where possible they would attend various dojos and undertake duelling and training in multiple weapons and different styles. In some cases, during their travels, some would accept work as school teachers, mercenaries, bodyguards and assistants to help pay their way.

This type of warrior training is said to have begun during the Sengoku, warring states period. At that time, in the midst of ongoing warfare, there was a growing awareness of the importance of honing one’s martial arts abilities, and while the main weapons of the samurai were the bow and arrow, the spear, matchlock guns, various pole arms and the sword, it appears that swordsmanship and the spear were the more popular of military training to undertake. Another reason for the musha shugyo was to secure employment. In the late Sengoku and early Edo periods, feudal lords in various provinces began to seek talented people. There were many samurai at the time who had become ronin, masterless samurai, often displaced through their masters having lost battles, amongst other reasons. These men all sought employment with the domains while aiming to improve themselves, and this duelling was a chance to make a name for oneself through such duelling.

These trainees or Shugyosha as they were called, travelled to various places around the country, engaging in duels or training with local masters, warriors of note and studying and teaching each other their military tactics. In this environment, various martial arts schools emerged and developed, and there was also considerable exchange and competition between the different schools.

The Sengoku period ended when the Tokugawa clan finally destroyed the rival Toyotomi clan of Osaka in 1615. With the fall of Osaka Castle, the Tokugawa achieved a relative peace that would last for around 250 years. As the Edo period progressed, and society became peaceful, order was finally stabilized, leading to the many military arts schools gradually becoming more conservative, to the degree that samurai began to avoid fighting with other schools, and so combat warrior training went into decline. During that time, the martial skills of the samurai sunk to depths not seen in over six decades. However, towards the end of the Edo period, from the 1830’s onwards, when various external threats came to be recognised — in particular, foreign naval and trading ships entering Japanese waters — warrior training and the military arts became popular once again. Programs promoting martial arts training intensified in most domains, and samurai from various regions again began to travel around the country (with permission from their domain so as not to be seen as deserters) and actively participate in combat training with other schools. The revival of warrior training deepened exchanges between domains at the samurai level and had a significant impact on the political situation in the late Edo period.

A range of documents have been passed down and serve as reliable historical materials providing information on the Shugyosha of the time. Records and diaries written by traveling trainees, such as the Shokoku Eimeiroku, Records of the Various Provinces, and the diary of Muta Takaatsu of Saga domain in particular contain detailed records of their training trips.

Muta Takaatsu’s Shugyo Diary

The diary of Saga Domain swordsman Muta Takaatsu, (aka Takatsune, November 24, 1830 - December 8, 1890) titled the Shokoku Kaireki Nikki, is one of the best-known surviving accounts of a Musha Shugyo, and is in the possession of the Saga Prefectural Library.

Along with the Shokoku Kaireki Nikki diaries, five volumes entitled Bumeiroku (only volume 5 is called Eimeiroku) remain. It includes a list the places he visited, and of the swordsmen he fought during his training. The diary is thought to have served as a report for when he returned to his domain.

In his writings Muta provides harsh evaluations of many of the schools he visited but gives relatively high evaluations of the practitioners of Shinto Munen-ryu and Tsuda Ichiden-ryu (In many cases he writes that he won 70 to 80% of his bouts).

At the time, the Saga domain would select promising samurai to study swordsmanship, spearmanship, and literature outside the domain on a yearly basis, and Takaatsu undertyook his Musha Shugyo from September 27, 1853 to September 1855, at the command of the Saga domain's lord, Nabeshima Narimasa (aka Naomasa). The route he took during this trip often overlaps that of Kumamoto domain swordsman Miyazaki Masakata, a disciple of Santo Hanbei of Niten Ichi-ryu had taken three years earlier.

Incidentally, Muta visited Edo in December 1853, where he was ordered to guard the Edo residence of the Saga Domain in January 1854 due to the arrival of the American navy Black Ships. During that time, he visited sword-fighting dojos across Edo and held matches. He visited Edo again in August 1854, and from October of the same year, he repeatedly challenged Chiba Eijiro of the Hokushin Itto-ryu to matches, but each time he was refused, with excuses such as "Today's training is over" or "I'm not feeling well," and he was unable to match Chiba. In his diary, Muta Takaatsu criticized Chiba Eijiro for this, calling him "the epitome of cowardice."

In the diary he comments that when he saw the frivolous dress sense of Akita domain samurai at a festival, he felt that such samurai were not true samurai.

According to the notes, he decided to go to Matsumae Domain (Hokkaido) to train, but on hearing of the possible arrival of more foreign ships, he gave up. Therefore, Takaatsu's training journey ended in the northern Tohoku region.

Other famous warriors known to have undertaken Musha Shugyo include Miyamoto Musashi, Sasaki Kojiro, Yagyu Jubei, Kamiizumi Nobutsuna among many more.

The Shugyosha would usually be dressed in upper kimono and hakama worn tied close to the shin below the knee, wearing a wide brimmed straw hat, possibly a striped heavy cloth cape in cooler climes, and carrying his meagre travel possessions in a webbed sack on his back. Often he may have, besides his two swords, a spear or a glaive-like naginata with him.

Musha Shugyo is believed to have been influenced by the ascetic pilgrimages of Zen monks in their pursuit of enlightenment. Although it was usually undertaken as a personal and spiritual improvement exercise, in some cases it was made through necessity, such as having been made a ronin, a master-less samurai, or for having breached laws or clan rules, in which case it was akin to exile. Many would undertake such a spartan quest in the hopes of being offered a position under a daimyo, or in order to be of better service to their liege lords.

Incidentally, in these modern times, students going to other areas or foreign countries to train in academics and the arts are also known as… Shugyosha.

One subject that is pretty obscure, possibly also due to the difficulty on finding reliable sources and archaelogical materials is how martial arts were taught during the Sengoku period. We know a lot about Doujos, schools etc. during the Edo period but so little about earlier centuries and especially during the height of the samurai as "true" warriors waging war.

I hope this will change due to scholarly efforts or even a "fortuitous" discovery. In the meantime perhaps a quote from a videogame (Elder Scroll Oblivion) might well describe what used to happen: "The best techniques are passed on by the survivors"

Something else I am intrigued with.... we now know that even the oldest ryu did not have much to do with battlefield training, from the emphasis on the sword in many of them, lack of group tactics, (most, not all, and recreation of older schools for group archery or gunnery is a question here)and various other reasons. Friday has probably addressed that best, as well as the battle reports we know from Conlan's research. Mark Hague's recent works on Itto-ryu contain some fascinating material on tonomo, teachings "outside" of actual physical techniques, often including things like overall life advice, mindset, strategy, tactics, general teachings of the time, etc. What is very interesting to me is the presence of things like how to deal with ambushes by multiple attackers, going through doorways, how to secure your campsite to keep from being snuck up on, how to set up a mosquito net in case you are ambushed when underneath it, how to tie off doors, how to capture armed barricaded people,(even Musashi writes of capture techniques (torite) for people "holed up.") and so on. It seems that many ryuha, rather than being a general "senjojutsu" (battlefield skills) were actually "musha shugyo jutsu" - skills not just for defeating rivals in challenges and duels, but how to keep from being ambushed and murdered by the followers of people you defeated, not to mention typical brigands and other ne-er do wells on the road, and how to manage some criminal situations when you were just passing through and called on to help, or were dispatched by the local lord to do so (as in the well known examples of Kamiizumi and Ono Tadaaki). To me its like they hit those bases more than simply dueling or gekken fighting skills.